Wind power plants (WPPs) can be considered “green” energy only when they do not harm nature.

Українська версія: Вітропарки у високогір’ях Карпат: користь чи шкода?

We all speak about the European choice, about preserving nature and developing “green” energy as a way forward to the future. But can we really call “green” the energy that, while producing electricity from wind, at the same time destroys the unique primeval forests of the Carpathians, eliminates rare species of plants and birds, and opens the way for large-scale construction on protected areas or along their borders? This very issue was discussed by scientists and environmentalists during the second Eco Film Festival by CHYSTO.DE?!. By presenting clear arguments, they sought to show why building wind farms in the Carpathians does not meet the principles of green energy and what threats it poses to ecosystems and the unique Carpathian landscapes.

“There are plans to place 1.5 GW of power generation in the Carpathians – specifically in the highlands”

Ecologist, Associate Professor at Uzhhorod National University, Oksana Stankevych-Volosyanchuk:

— Renewable energy must first and foremost be nature-friendly. It can only be called “green” when it does not harm wildlife. Why is it important to consider this issue from this perspective? First, we need to recall why we are developing renewable energy at all. This is one of the goals of the European Green Deal, which Ukraine has joined as a candidate country and future EU member, making its contribution to achieving Europe’s climate neutrality. Ukraine has significant potential in this field, and wind energy is part of it. By developing renewable energy, our country is in fact helping Europe achieve its main goal — climate neutrality.

But that is only one side of the coin. The other is the preservation of natural ecosystems. They are the main and unique absorbers of greenhouse gases on the planet. Therefore, in tackling climate change, natural ecosystems are of primary importance. They must be prioritized in any discussions about whether or not to build renewable facilities on valuable natural territories. Why so? Because no matter how much energy capacity we build, greenhouse gas emissions will still exist. Only natural ecosystems, primarily plants, are capable of absorbing them. Achieving “net zero” is possible only if there are enough preserved natural ecosystems on the planet that can absorb carbon dioxide and other emissions. That is why biodiversity conservation is key to achieving climate neutrality.

Video from Runa Meadow. Author withheld for security reasons.

This is also reflected in the European Green Deal: by 2050, EU countries must ensure the protection of 30% of land and 30% of marine areas. Currently, 10–20% of land in the EU is under protection, while the situation with marine territories is worse, but the targets are clearly defined. Moreover, an additional 20% of transformed land must be restored to its natural state.

It is important for Ukrainians to recognize this as well: when we talk about the development of renewable energy sources, we must also understand the context of preserving valuable natural areas. In Ukraine, they cover only 7%. We have committed ourselves to the EU to increase the share of protected areas to 30% by 2030. However, it is already clear that with the current approach we may not only fail to reach this target, but also risk losing what we already have.

Today, there are plans to place 1.5 GW of power generation in the Carpathians. This concerns the highlands — a narrow strip of territory with seven mountain ranges. In the Carpathians, highlands are considered elevations starting from 1,300 meters above sea level. These are special natural conditions similar to tundra: alpine and subalpine zones, the so-called mountain tundra. These are the least developed territories in Ukraine, unique in their landscapes, the most preserved, remote from settlements, surrounded by protected areas, dense forests, and primeval forests. There are no roads there, and access is difficult. It is precisely in these areas that wind turbines with a total capacity of 1.5 GW are planned to be installed, which would effectively turn unique natural landscapes into an industrial zone.

Discussion at the Eco Film Festival by CHYSTO.DE?!. Photo by Vlada Mazur

Moreover, most of these territories already hold the status of Emerald Network sites or are candidates for it. The state has officially recognized them as extremely valuable for both Ukraine and Europe. However, construction here would mean the loss of rare habitats, a threat to bird and bat biodiversity, as well as the disruption of migration corridors for large predators — bears, wolves, and lynxes.

At the same time, it is worth noting that the situation is not the same everywhere. In the Carpathians, there are positive examples of wind farms operating outside the Emerald Network, such as in Staryi Sambir, the Truskavets territorial community in Lviv region, and the Nyzhni Vorota territorial community in Zakarpattia. These were built on territories that have no significant natural value.

By contrast, construction in the mountains is always complex and expensive: new roads must be built, the difficult terrain must be overcome, and this inevitably impacts the environment. On the plains, everything is much simpler and cheaper — infrastructure already exists, a foundation pit can be dug in a single day, and construction proceeds much faster.

Therefore, it is important to speak about clear criteria for placing wind farms in mountain regions. The first and main criterion is the presence of wind potential. However, the Global Wind Atlas shows that the greatest potential lies in the eastern and southern regions — partly inaccessible due to the war, but there are other territories suitable for development. In the Carpathians, wind potential is limited to narrow strips of high-altitude ridges, where nearly as much capacity is planned to be installed as was operating across all of Ukraine before 2022. However, this seems unreasonable when comparing harm and benefit.

Two other significant criteria are proximity to urbanized areas without natural value and the availability of developed infrastructure — roads, power lines, and so on. The Carpathian highlands do not meet these criteria, as they consist of valuable natural territories — Emerald Network sites, and are centers of unique Ukrainian landscapes and biodiversity. These are wild areas without roads or power lines, with only shepherds’ huts. To reach these alpine meadows, roads would need to be cut through continuous forests, primeval forests, and protected areas.

In other words, in the case of wind farm projects in the Carpathian highlands, only one criterion is met — the presence of wind; all the others fail to hold up to any scrutiny.

Currently, there are three wind farms in the Carpathian region that can be considered successful. For example, the Nyzhni Vorota wind farm, now the largest in the mountain areas of Ukraine, is located next to settlements and the international Kyiv–Chop highway, on long-developed territories. The Staryi Sambir wind farm was built at an altitude of 400–500 meters above sea level, also not far from a village. The Oriv wind farm in the Truskavets community stands at 700 meters, along an old road connecting neighboring villages, but the community deliberately refused to expand the project due to the risk of losing its tourist appeal.

As for international experience: in Poland and Slovakia, wind energy in the Carpathians is not being developed at all — there are no wind farms there. In Romania, which is also a mountainous country, there is only one high-altitude wind farm in the Apuseni Mountains, consisting of four turbines at an altitude of 1,600 meters. This is also explained by geological differences: the Carpathians in Ukraine are flysch mountains with fragile rocks prone to landslides, erosion, and mudflows, while the Apuseni are similar to the Alps and the Balkans, composed of solid rocks. This particular feature of the mountains explains the presence of a network of roads across the entire Apuseni range. In our conditions, however, road construction is far more problematic.

Therefore, once again it must be emphasized: wind power plants built in the highlands of the Carpathians, with the significant environmental impacts outlined above, cannot be called “green.” The damage caused by building wind farms in the highlands cannot be compared with the benefits of generating electricity.

“The Carpathian highlands are no-go areas for wind turbines”

Marine Abramian, Campaigner at Greenpeace Ukraine:

— When speaking about the benefits of wind energy, I want to voice the position of Greenpeace in the context of what is happening in the Carpathians today. We fully support those who are fighting to keep the Carpathian highlands free from any kind of development — whether wind power plants or projects like a “new Bukovel.” This is unacceptable. And we stand in full solidarity with those in Zakarpattia who are defending nature today.

Now, as to why wind power plants (WPPs) are still important — Greenpeace supports the development of renewable energy in Ukraine. All of us who have lived in Ukraine since 2022 know what it means to be left without electricity. The inability to cook food, heat your home, or charge your phone. Electricity is vital.

When, as a result of Russian actions, we lost most of our electricity generation, the first solution for many was to use diesel and gasoline generators. It seemed like a cheap and accessible option, so people bought them en masse. But soon we all experienced the problems — fuel shortages, noise, and fumes. This is how the autumn and winter of 2022–2023 were remembered in Kyiv, for example.

That is why I was very glad later to see that some small businesses started equipping their cafés and shops with solar panels. This became a more sustainable and responsible solution. We are now living in a period of transition to green energy. The full-scale war has only accelerated this process: with the loss of more than 70% of electricity generation, Ukraine was forced to look for quick solutions — and many of them turned out to be green.

In 2024, the share of electricity from renewable sources in our energy mix reached about 11%. This is an excellent result, even though the data is most likely underestimated: many private households installed solar panels on their own without notifying grid operators.

Nevertheless, the need for large-scale generation facilities remains. And wind power plants (WPPs) can become one of the key solutions.

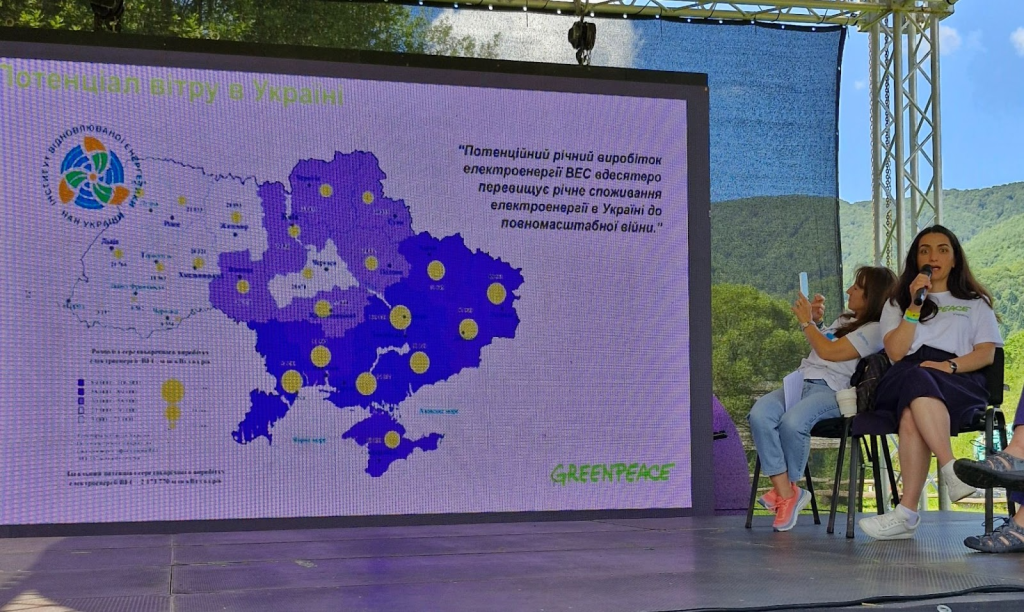

Greenpeace, together with colleagues from the University of Sydney, conducted a study on Ukraine’s wind potential, which confirmed the significant prospects of this type of electricity generation for the country. But to be as objective as possible, let us look at the wind potential map from a study conducted by the Institute of Renewable Energy of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

On the map, where zones are color-coded (dark purple — significant wind potential, white — low potential), it is clearly visible: Zakarpattia is “white,” meaning it has the lowest wind potential among all regions of Ukraine. This is logical, as Zakarpattia is surrounded by forests and mountains, which are undeniable obstacles to the development of wind energy (forests are a natural barrier to wind flows, while mountains complicate the construction of roads and power lines). This is the Carpathians — they consist precisely of forests and mountains. Just like our own research, this confirms that Ukraine has enough territories suitable for wind energy development — and these are not the Carpathian highlands.

If we take into account Europe’s experience in this matter, there are two approaches: go-to areas and no-go areas. In other words, at the legislative level, zones are defined where building wind farms is acceptable, and those where it is strictly prohibited. If an investor wants to build a wind farm, they can simply look at the “go-to areas” map and see where it is possible. By contrast, primeval forests, nature reserves, and peatlands are “no-go areas,” and every investor must understand that their project will be stopped there. It is very important to recognize that those who attempt to pursue such projects in these zones will face problems — both legal challenges and negative community responses to the idea.

Another significant aspect is wind corridors. Indeed, the steppe regions of Ukraine are the areas where building wind farms is reasonable. However, the lack of proper infrastructure for transporting equipment significantly reduces the likelihood of construction in these territories. Turbine blades are extremely large, and not every road in Ukraine is suitable for transporting them.

Local communities must play a key role in processes related to the construction of wind energy facilities. Not only environmentalists or activists, but residents themselves. They should be interested in ensuring that the land serves them and their descendants. In many countries, there are energy cooperatives where communities become co-owners of energy facilities. This provides a balance between development and the protection of people’s interests and the environment in which they live.

Therefore, Greenpeace supports the development of wind energy only when the choice of territories for wind farms takes into account the interests of both nature and local communities. Only in this way can we move forward while preserving what is most valuable.

“This is a predatory approach to the Carpathians”

Kateryna Polyanska, environmentalist at the NGO Ecology. Law. Human:

— In eastern and southern Ukraine, we have already lost a vast amount of valuable natural land. Agricultural areas cover 73% of the country, of which 56% are ploughed fields. We aspire to join the EU, and there we are told: “You must preserve nature, you must create protected areas.” And what are we doing instead? If you look at the entire territory of Ukraine, the Carpathians account for only 4% of the state’s area. Of this, just about 3% falls within the alpine and subalpine belts — relict meadows, remnants of the last Ice Age. These are areas that absolutely must be protected! And yet, what do we do? We bring business into them!

Business representatives argue that only small patches of land along the ridge will be built on, not the entire ridge. But they remain silent about the fact that constructing a wind farm takes several years, during which heavy machinery will move back and forth across these “small patches,” carving out a whole network of roads. Has anyone considered how to transport a 20–30 meter blade up a mountain ridge? All these areas are surrounded by primeval forests and protected lands — and wide roads would have to be cut through them. So when they say there will be no damage, that is simply not true.

My colleagues and I visited Mount Troyaska in the Svydovets range, where a wind-measuring tower has already been installed. It broke my heart, because earlier we had been studying the environmental impact of military actions, and the picture was almost the same: an excavator tearing up the earth just like the occupiers digging trenches. Species listed in Ukraine’s Red Book were destroyed there, and the soils damaged.

Developers insist that all these structures are temporary, like the tower. But the roads, the foundations, the power lines — both underground and aboveground — form a whole infrastructure for operating a wind power plant, and that will devastate nature.

Runa Meadow (in Ukrainian: polonyna Runa) is another example. These are unique landscapes. Yes, there are already a few roads and the remains of a former Soviet communication network on one of the peaks. But when developers point to those remnants of urbanization as justification and then propose three dozen new industrial sites with a whole network of roads, the scale of human impact becomes far greater than anything Runa has ever experienced.

Can this really be called “green energy” if it destroys nature instead of protecting it? Especially since we are talking about areas of primeval and near-primeval forests. Building there is simply impossible, as these territories are adjacent to ornithological reserves. Birds that feed outside the forest fly precisely at the heights where the turbines will spin. Scientists warn: this will inevitably lead to mass bird deaths.

Runa Meadow. Photo by Anna Semeniuk

Another problem is the soil. Construction tears open mountain slopes, triggering erosion processes. These lands cannot be restored — you can’t just fill them in and “make them as they were.”

That is why we are categorically opposed to such a predatory approach to the Carpathians. This must be stopped before it is too late.

“Can a single village council hand over such valuable land without taking national interests into account?”

Head of the Legal Department of the international charitable organization Ecology–Law–Human, Olha Melen-Zabramna:

— It’s frustrating that this happens so often: investors come in thinking that legal requirements are not a problem, international conventions are not a problem, local people are not a problem, and environmentalists are not a problem either. Because yes, there are professional and conscientious environmental experts — but you can always pay others, and they’ll produce the kind of Environmental Impact Assessment report that says everything is fine. We very often face situations where such plans begin to move forward, and as lawyers, we realize we must act. We have to defend our mountains, protect the highland meadows. Over the last ten years, we’ve been working actively to shield both the Emerald Network sites and the protected areas (nature reserves) from this kind of unlawful activity.

The largest number of destructive projects are appearing in Zakarpattia region, with fewer in Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk. In Zakarpattia, this is not the first mega-project that threatens to destroy unique high-mountain landscapes. The first was an attempt to build over the Svydovets ridge, covering 1,200 hectares. Since 2017, we have been fighting this project in the courts — the battle has lasted almost eight years.

We already have a Supreme Court ruling that the detailed plan was unlawful. Supporters of such projects are often local council heads, who openly say: “We need any investor, we need roads, so we’re not interested in your environmental arguments.” It is very difficult to convince local residents that the impacts of building on highland meadows will have long-term consequences for both the environment and their well-being. For example, thirty wind turbines on the Runa meadow would make this area completely unattractive for tourism. All other forms of recreation and income would be lost, which contradicts the land-use planning schemes of Zakarpattia region and the corresponding district. Yet the village council is still eager to bring in these investors.

As for the investors, they lease only small plots for the wind turbines — about 0.6 hectares per unit, or just over 18 hectares in total for 30 turbines. But in reality, more than 1,200 hectares of the Runa meadow will be used — exactly as stated in the detailed plan for the wind farm’s location. Yet these 1,200 hectares of lost land will not be compensated to the community; they will simply be taken out of use. This is a clear manipulation of figures. No one specifies how many hectares will be allocated for access roads, how much forest ecosystem will be destroyed to lay power lines, or how much land will be lost to road construction between the turbines.

The financial return is also highly questionable. The losses in ecosystem services caused by the destruction of old-growth forests, endangered biodiversity, and unique landscapes are not being counted. This raises a key question: can a single village council make decisions of such global significance? Legally, the council does have the right to approve a detailed land-use plan. But should it be allowed to hand over such uniquely valuable territories without taking into account national interests and Ukraine’s European integration commitments? The highlands and their biodiversity are the common property of the entire Ukrainian people.

On August 21, 2025, the Zakarpattia District Administrative Court, presided over by Judge Yaroslava Kalynych, announced its ruling in case No. 260/5885/24, filed by the International Charitable Organization Environment–People–Law against the Turya-Remety Village Council. The case involved third parties without independent claims: Turyansky Wind Park LLC (on the side of the defendant) and Nataliya Maistrenko (on the side of the plaintiff). The lawsuit concerned the recognition as unlawful and annulment of the Village Council’s decision to approve the detailed spatial plan (DSP) for the construction of a wind power plant on the Runa meadow.

The court dismissed EPL’s claim, effectively refusing to defend the unique Carpathian highlands and leaving in force the document that paves the way for the development of the Runa highland meadow with wind energy facilities, despite clear signs of gross legal violations.

The ruling of the Zakarpattia District Administrative Court appears more political than legal — an attempt to lend a veneer of legitimacy to the activities of Turyansky Wind Park LLC in constructing a wind farm on Runa highland meadow without a positive environmental impact assessment (EIA) and in breach of both international obligations and environmental protection laws.

By its decision, the court also turned a blind eye to the arbitrariness of local councils, which are attempting to dispose of particularly valuable lands at their own discretion—ignoring state policy, national urban planning documents, and Ukraine’s international commitments to protect wildlife and natural habitats.

Defenders of nature and of Runa meadow are being portrayed as enemies of green energy and even accused of serving the aggressor state. Representatives of the developers employ manipulative, opaque, and cynical tactics, revealing that their true aim is to push through construction on Runa meadow at any cost. Such development would destroy nearby protected areas, make it impossible to designate the territory as a planned Emerald Network site, and also question the possibility of achieving the conservation goals of the Sokolovi Skeli reserve.

That is why we will continue to defend Runa meadow. This struggle goes far beyond the local context — it is a fight for the future of the Carpathians and is directly tied to Ukraine’s European integration commitments: creating the Natura 2000 network, protecting biodiversity, and ensuring citizens’ right to a safe and healthy environment.

This conversation took place as part of the Eco Film Festival by CHYSTO.DE?!

Dialogue recorded by — Tetiana Kohutych

Editor — Olena Zhuk

Translation — Mila Moroz

Photography – Vlada Mazur, Anna Semeniuk